Of Pigeons, Palaces, Mutts and Kings

“Twenty years from now you will be more disappointed by the things you didn’t do than by the ones you did. So throw off the bowlines, sail away from the safe harbor. Catch the trade winds in your sails. Explore. Dream. Discover.”

Babulal, the cab driver, is a resourceful man. He’s born and raised here, a son of this sandy earth, he’s grown up with the folklore, he knows all the back roads, the shortcuts, the out of the way places, he’s proud of this land he calls home. We tell him we want an authentic Rajasthani lunch. Nothing fancy, we say. The kind of food you would enjoy yourself. He smiles and says he knows just the place. Ker sangri, kadhi, and gud with bajre ki roti. Washed down with a sizeable quantity of chhaas. At a roadside dhaba in rural Rajasthan. This has to be, without a doubt, one of the best meals I’ve ever had. Simple, delicious, generous, and served with a smile.

Several years ago, I started putting together a bucket list of places I must visit before I die. Some of those places are right here in India, and I’m not very proud of the fact that I haven’t checked them all off. Rajasthan is one of those places. This is probably one of the most visited parts of India, by travelers from within the country and from foreign lands, it commands fat chapters dedicated to it in just about every guidebook ever written about India, and, as I found out for myself, all for a very good reason.

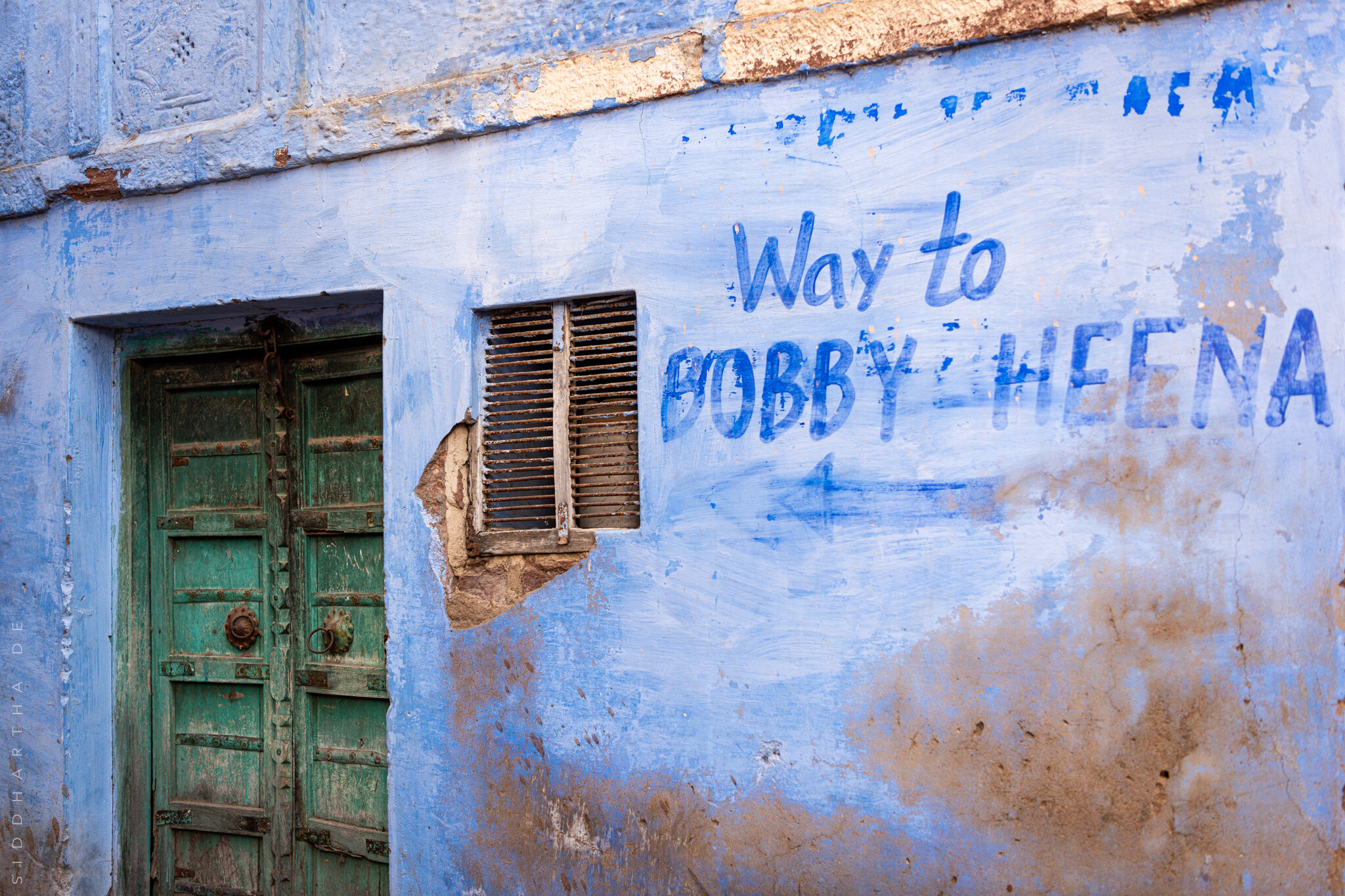

Our Rajasthan experience started in Jodhpur, the Blue City of India. For years I had been drawn to the pictures that other people had made in this charming town at the foot of the imposing Mehrangarh Fort, pictures in that iconic shade of blue made famous by photographers like Steve McCurry. I wanted to see it for myself. I NEEDED to see it for myself. So, amid the cacophony of the streets around Ghanta Ghar, the old clock tower, we haggled with autowallahs who probably have never used the meter in their lives, we pondered our next move over a cup of tea in Sardar Market, and weighed different options to find the best one to explore the Blue City. We were cautioned that it won’t be easy to find our way through this part of the old town, so we decided to sign up for a walking tour. Excellent advice, and I’m glad we took it. Our guide was enthusiastic and knowledgeable, he took us through a maze of lanes and alleys we wouldn’t have found on our own, and I saw more blue walls in a couple of hours than I had seen in my entire life.

This is probably one of the most visited parts of India, by travelers from within the country and from foreign lands, it commands fat chapters dedicated to it in just about every guidebook ever written about India, and, as I found out for myself, all for a very good reason.

I found myself wandering away from the group more than a few times in search of a picture. I saw a girl walking up the alley in front of me. It didn’t make for a very interesting photograph. I was looking for something that screamed ‘Jodhpur!’. Something preferably with a blue wall and a red turban in the same frame. Suddenly the girl turned left, walked up some steps, took her chappals off and went in through the door. There was something about the iridescent green hue of her chappals that caught my eye. I moved to get a better perspective. She must have been waiting for someone else because she came back out to look around when she spotted me. Seeing my camera, she shyly withdrew behind the relative safety of the door while still keeping an eye on me, giving me one of my favourite shots from that afternoon.

I took pictures of autowallahs in their brightly painted tuk-tuks, young girls in vivid dresses that contrasted with their blue homes, ladies in red and orange saris, their pallus pulled over their faces like a veil, unflappable gents with their imposing turbans and proud moustaches, and the ubiquitous Jodhpur mutts. They’re everywhere, some of them bold, some reticent, some indifferent to our presence.

We spent a few hours walking around this old part of Jodhpur, but it wasn’t nearly enough. There was so much more to see in this part of the city, and not enough time to take it all in. The guide told us that Jodhpur has been getting less blue over the years, that the old traditions and historical reasons for the houses being the beautiful shade of blue they are, are not as relevant today as they were in the old days, and people are simply opting for any other colour that strikes their fancy. What a pity. I hope that UNESCO or the Archaeological Survey of India designates this quarter of Jodhpur a protected area so that these blue houses can be better preserved.

We went to Mehrangarh Fort, easily one of the most imposing and beautiful historical monuments in India. Pictures do not do it justice. You have to go there, see its sheer scale and majesty as it watches proudly over the city. If you want to experience something that is as colossal as it is delicate, and as invulnerable as it is beguiling, it is here that you’ll find it. That something made of gigantic chunks of stone could be shaped into something so beautiful, using tools from centuries ago, is a wonder in itself, and spending the afternoon walking around the cool courtyards, through the royal chambers that are now part of a museum, through the colonnaded corridors, and along the ramparts and turrets with their gigantic cannons, to soak in the grandeur of the place is an unforgettable experience. So much, that it was the only spot on our Jodhpur itinerary that we visited twice during the four days that we were there. Oh, and the pigeons. There’s something about historic sites in this country that attracts these birds by the thousands, and every so often one hears the flapping of a thousand wings as they all take to the air on a cue that only they understand.

We paused for a break at one of the cafés within the fort, and to take a load off my back (camera equipment can be heavy!). We were in a courtyard surrounded by the high walls and filigreed windows of what must have been the zenana, the ladies’ chambers, from where the queen and her handmaidens must have observed the goings-on below. I watched a thief going about his business on the unoccupied table next to ours. He was alert to our presence but was not to be detracted from the task at hand: to steal the packets of sugar that were kept on the table for customers. He was interested in only the organic brown sugar, not the refined white stuff. Even thieves have standards.

We walked to the Jaswant Thada, the elegant marble mausoleum that is the final resting place of Maharaja Jaswant Singh II. It’s a peaceful and beautiful place, commanding a splendid view of both the fort as well as the city. We spent some time here, in the cenotaph itself and in the gardens and along the lake surrounding it. We walked around, looking for a suitable spot to take a picture of the sunset. And everywhere we went, the pigeons, in their thousands, were all around us.

We ambled through the market in central Jodhpur and haggled with the merchants who sold handmade wicker baskets, handlooms and lacquer bangles. We drank creamy muskaani lassi at Mishrilal Hotel, stuffed giant gulab jamuns into our faces at Mohanji Mithaiwale, demolished fat mirchi wadas at Janta Sweet Home, and put away impressive portions of laal maas at Indique and Dhani. We walked around the Gulab Sagar, sat on the steps of Toorji ka Jhalra, the ancient step-well in the heart of the city, and had a beer at the café overlooking the step-well itself. We met and befriended other travelers, we ate and drank everything Jodhpur had to offer, and we packed a week’s worth of activity into four days. But now it was time to head to Jaisalmer and the sand dunes of the Thar Desert.

Babulal drove us there. He occasionally offered us a nugget of information about something or the other, the trees from which sangri is harvested, or the fields of cumin, or the area around Pokhran where nuclear tests had been conducted in the 90s, or the date farms from where one can buy fresh dates along the road. Jaisalmer is called the Golden City of India, and one can see why even from a distance of 20 or 30 km outside the city when the impressive fort comes into view. The fort and the buildings of the old city are made of a type of sandstone with a peculiar golden lustre that reflects the sunlight and the sandy environs. Jaisalmer Fort is a living fort, in that it has been continuously inhabited since it was built in the 12th century.

We had decided to stay within Jaisalmer Fort itself in a charming haveli that had been converted into a heritage hotel. Since cars cannot get into the narrow cobbled stone lanes within the fort, Babulal dropped us off outside, from where we hired a tuk-tuk to take us and our belongings up to the hotel. We were high over the city, a spectacular view looking east over the Gadisar Lake. Jaisalmer is a small town, something I took advantage of when I rose early every morning to walk down the narrow winding streets to the edge of the lake to catch the sunrise as it broke over the city. And every morning, I walked to the pealing of temple bells and the aazaan from nearby mosques, always accompanied by a group of curious mutts, their tails wagging as they hoped perhaps for a scrap or two as they walked alongside me to the temples and ghats along the edge of the water. The shaded chhatris, home of course to scores of roosting pigeons, some distance into the lake provided me with a nice foreground against the sunrise. The sunrise duly photographed, I returned to the fort and climbed the steep stone path to the hotel for a delicious breakfast on the roof every morning that fueled us for the day ahead.

We got caught one morning (not entirely unawares or against our wishes) in a raucous Holi celebration that is unique to the community that lives within the fort. The fort is home to a temple that is one of the most important in Jaisalmer, and every year the elder from the pujari’s family (the head pujari of the temple has come from the same family for centuries) is crowned king of Jaisalmer for a day. There is a coronation ceremony that everyone, local and visitor, participates in, the streets are a riot of colour, and the air is a dense cloud of gulaal. Nobody is spared, not the tourists, not the local boys and girls, not their grandparents, not their cattle, not the shopkeepers and autowallahs, not even the local mutts who call the fort home. Later, while the city descended into the lull of a bhaang-induced stupor, we slipped out and had Babulal drive us out into the desert for a date with Jamal and his camels.

On the way, Babulal recommended that we stop to see the ruins of the abandoned village at Kuldhara. He told us the story of the abandoned village, which I thought was more interesting than the village itself. Legend has it that a local minister, Salim Singh, fell in love with a girl from Kuldhara. The minister belonged to the Kshatriya (warrior) caste, while the villagers belonged to the high Brahmin (priest) caste, and it was forbidden in those times for people from these different castes to marry. Knowing that the minister would try to take the girl by force, the entire village packed their belongings and fled overnight. All that is left today are the old ruined buildings and cobbled streets, a medieval ghost town still standing in the stark countryside. We spent an hour or so here and went on towards the dunes, about as far west as one can get in India, towards the border with Pakistan.

It was almost as if the day had had enough of the colour of the morning. Dark, ominous clouds rolled in, we had a brief spell of rain, rare in the desert, and I was worried that I wouldn’t be able to photograph the sunset I had come so far for. I was hoping to get an expansive shot with the dunes at sunset, the light dancing around the ridges and contours in the sand, and with preferably a camel or two in the frame as well. But the weather had other ideas. We toyed with the idea of abandoning the plan altogether and coming back again the following day, but we pressed on, and reached our rendezvous with Jamal and his brother about an hour before the sun went down.

And every morning, I walked to the pealing of temple bells and the aazaan from nearby mosques, always accompanied by a group of curious mutts, their tails wagging as they hoped perhaps for a scrap or two as they walked alongside me to the temples and ghats along the edge of the water.

Jamal led us into the dunes. It was still cloudy and grey, and I was all but resigned to the prospect of not getting the golden sunset I had hoped for. I went off in search of something else to take a picture of. And just then, I noticed the light changing. I turned around and saw that the setting sun had broken through a gap in the clouds, throwing brilliant rays of beautiful golden light down onto the dunes. Jamal, his brother and the camels, who had been following us at a distance, were silhouetted on top of the dune. Perfect! We walked on a little further, then sat down to rest for a while. Jamal gave me his number and made me promise that I would send him the photographs I took. We chatted with him for a while, we asked him about his life in the desert, in the little village not far away that is his home, we asked him about what he does during the summer, the off-season, we asked about his kids. And while we were talking, it quickly started getting dark and cold, as it does in the desert. Jamal took us back to where Babulal was waiting to take us back to Jaisalmer. After a dinner of daal bati churma and bajre ki roti, the fatigue brought on by an eventful day caught up with us, and it was time to get to bed.

We spent the following day pottering around Jaisalmer, eating at some of the places we had heard about, shopping in the narrow lanes of the fort, and going out to the chhatris at Bada Bagh on the outskirts of town. This large windswept desert is home to hundreds of giant wind turbines that dot the landscape, and they provide an unusual contrast to the ancient monuments they tower over. We took a last long walk through the fort, wondering when we’ll have the opportunity to come back here again.

The end of our trip to Rajasthan was full of foreboding as the world started to come to grips with the COVID-19 epidemic that was sweeping across it. For a state that is not an agricultural or industrial powerhouse, and that depends on tourism for much of its revenue, the restrictions that would soon become the norm throughout the country would hit the people of Rajasthan particularly hard. Good, simple, hardworking, gracious and friendly people like Babulal and Jamal, like the guides and autowallahs and shopkeepers we met. We said goodbye to Babulal when he dropped us off for the last time, and his only request was that we ‘provide good feedback’.

A few days after I got home to Bangalore, I kept my promise to Jamal. I was pleasantly surprised when he and his son gave me a call the very next day to thank me. He seemed a bit worried. I hope he and his family are not hit too hard by this pandemic, that they see this through without too much difficulty, and that he’ll still be there on the dunes when I go to Rajasthan the next time.

What a trip! It was everything we had hoped for and so much more. Rajasthan isn’t a one-trip destination, and a week in this fantastic place was never going to be enough. It is so vast, and there is so much to take in, the beauty, the history, the architecture, the people, the culture, the food, that it will take months to do it proper justice. So, it will remain on my bucket list because there is just so much more to see in this fabled land of forts and ruins, of deserts and lakes, of pigeons, palaces, mutts and kings, of wonderful people and delectable food. Simple, delicious, generous, and served with a smile.